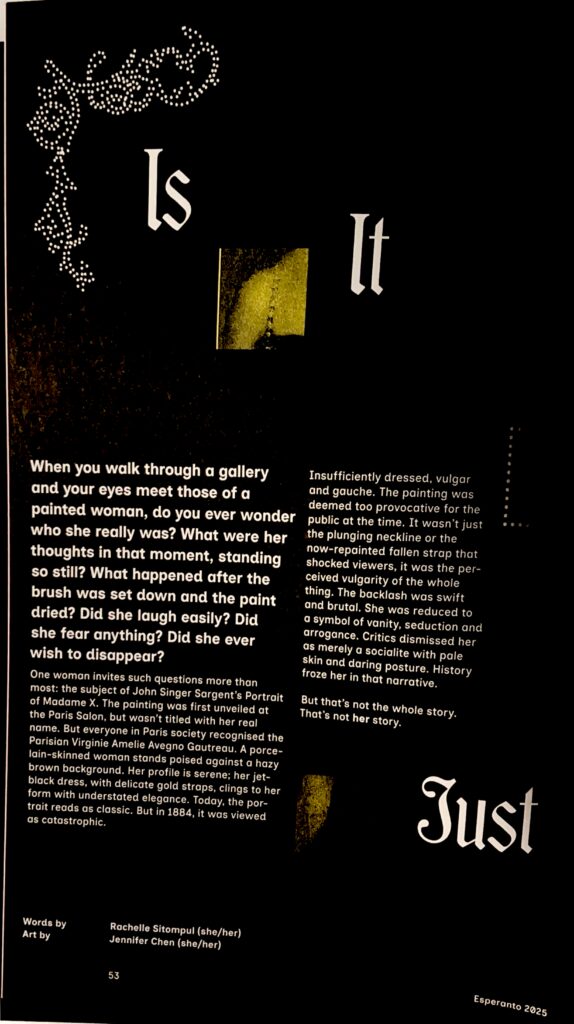

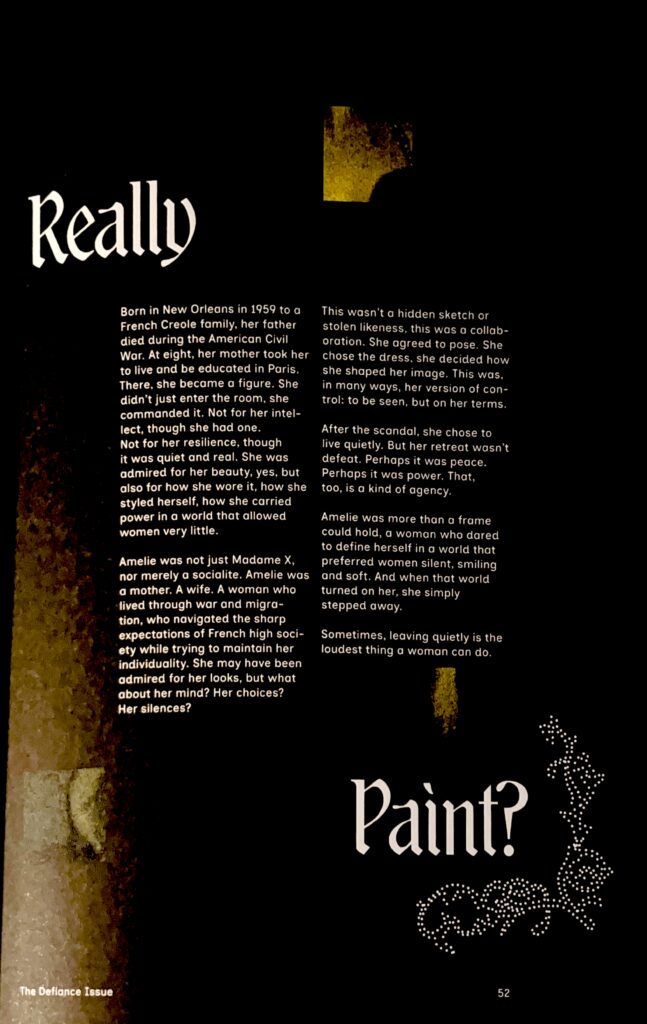

Contributed “Is It Really Just Paint”, a reflective piece exploring how art goes beyond aesthetics to become a medium of identity, expression, and meaning within Esperanto’s Her Series.

Read here: https://esperantomagazine.com/2025/09/09/is-it-really-just-paint/